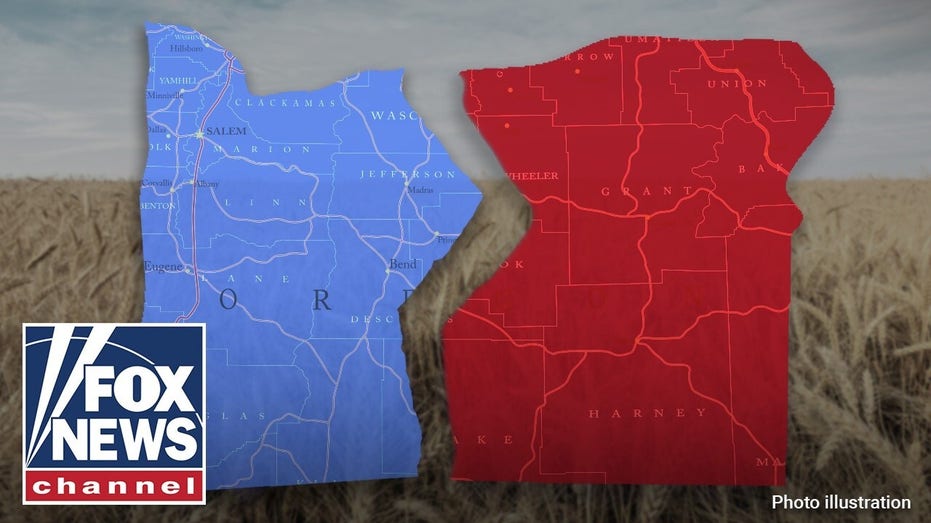

The Greater Idaho movement intends to break the Beaver State’s easternmost counties away and make them part of Idaho, which many on the right approve of.

Oregon’s ideological fault lines exposed during the anti-police riots of 2020 are again coming to the fore, as the Greater Idaho movement looks to sever the conservative geographic majority of the state from the urban progressive movement.

“This movement has always been about the people of Eastern Oregon, getting their voice heard and helping those communities get the kind of state-level governance they actually want,” executive director Matt McCaw told Fox News Digital.

“If the Oregon Legislature truly believes in democracy, they will honor those voters’ wishes and move forward on making a border change happen.”

But similar attempts at secession have produced mixed results in U.S. history.

Earlier this month, state Rep. Mark Owens, R-Malheur, put forward HB 3844, the measure that creates and directs a task force to document the impacts of relocating the Idaho border to include about 13 eastern Oregon counties, and requires a report be presented to lawmakers in Salem. He did not respond to a request for comment.

GREATER IDAHO MOVEMENT GAINS MOMENTUM

The Greater Idaho movement began putting such measures up for votes in various localities in 2020, and efforts have intensified as several incidents and issues in the geographically smaller but denser-populated coastal region have caused political divisions.

During the anti-police riots of 2020, Oregon was front-and-center as protesters vandalized Portland and made a dayslong violent stand in front of the Mark Hatfield Federal Courthouse. But in the eastern two-thirds of Oregon, the conservative geographic majority of the state does not often ideologically align with their urban brethren.

Greater Idaho president Mike McCarter said of the new legislative development: “We are encouraged to see the representatives of Eastern Oregon coming together to advocate for their voters by bringing these bills to the Legislature. The people of Eastern Oregon have made clear they want to explore moving the border and joining Idaho.

“This movement has always been about the people of Eastern Oregon, getting their voice heard and helping those communities get the kind of state-level governance they actually want.”

By shifting the border, proponents believe both states have a “win-win” – in that the people living in each would better reflect the established political majority and lower political tension.

NY LAWMAKER CALLS FOR STATEN ISLAND TO SECEDE

A report in the Central Oregonian noted an “interstate compact” is part of what is required to move the line, and cited other border-shifting bills in other states.

One would forward the cause of adding several rural Illinois counties that don’t see eye-to-eye with Springfield or Chicago to more closely aligned Indiana. Another in Iowa would allow the same movement for counties in the Land of Lincoln that are closer to the Hawkeye State line.

Idaho GOP Gov. Brad Little and Oregon Democratic Gov. Tina Kotek did not respond to requests for comment.

So far, only a few such movements regarding either secession or redrawing of state lines have been successful.

The now-55 counties of West Virginia voted to secede from the then-Confederate Virginia and independently ratified the U.S. Constitution on June 20, 1863.

A Washington Post story on the matter said Mountaineers split from Virginia as a way of “defending the ‘United States’… rather than the ‘seceded states’.”

In New York City’s Staten Island – the “forgotten borough” as many locals call it – there has been a movement afoot for decades seeking to break from the Big Apple.

Already geographically distant on the “New Jersey side” of the Hudson River, the borough is also separated from the Garden State by the Kill Van Kull and Arthur Kill.

Efforts to reestablish the reliably-red borough as the city of Richmond (after its coterminous county) or other names began with a favor from then-Gov. Mario Cuomo in the 1980s.

Cuomo enraged city leaders but endeared himself to the working-class voters on the island by approving state Sen. John J. Marchi’s push for a secession referendum.

Marchi, who died in 2006 and now has a Staten Island Ferry named in his honor, saw his borough vote nearly 2-1 to secede in 1993 – only to have their desires quashed by Albany’s Democratic majority.

And while the 1995 election of Mayor Rudy Giuliani calmed secession tensions, the drumbeat began anew in recent months.

“I think it’s time to secede,” Rep. Nicole Malliotakis, R-N.Y., told The New York Post as Gov. Kathy Hochul was touting her congestion-priced driving fee that now double-taxes Staten Island commuters.

“There’s no real value in being part of this city or the state. We didn’t vote for this mayor; we didn’t vote for this governor; and we didn’t vote for this president (then Joe Biden), but we’re always the ones getting screwed,” she said.